The “new” Orange Crush Mini 3W combo amp has an external speaker jack on the back. The amp sounds great through an external speaker, especially when it comes to edge-of-breakup tones. Plus, it can do higher gain tones at low volume. But, what if you have the original Orange Micro Crush that only has a headphone jack on the back?

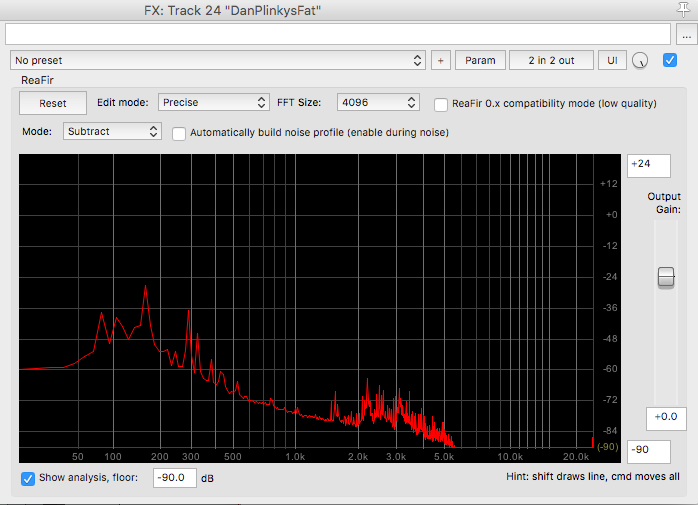

Well, it turns out that the internal speaker of the Micro Crush is wired through the headphone mini jack, which means that you can connect the amp to an external speaker using an 3.5mm male to 1/4” female jack adapter. I have tried this using a Vox 8” open back speaker cabinet and a Marshall 12” closed back cabinet, and it sounded best with the larger closed back cabinet. There seems to be some low frequency roll off in the amp, maybe to voice it for the small internal speaker, so running the amp through an external speaker works best for lead tones.

New gear is awesome, but sometimes new and exciting sounds can be found by experimenting with old gear, or cheap gear, or toys, or junk, or that thing that you left in a drawer for years.

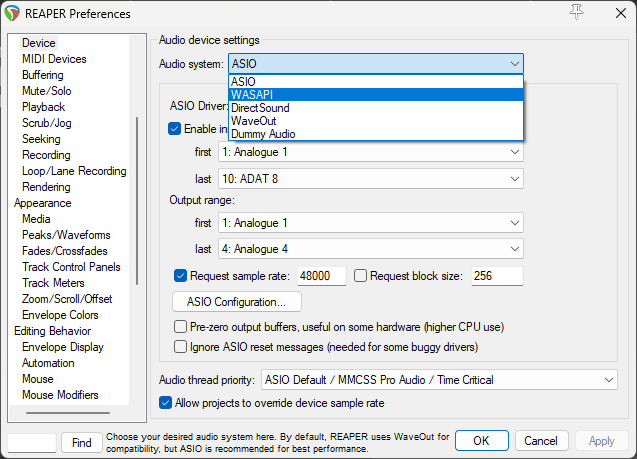

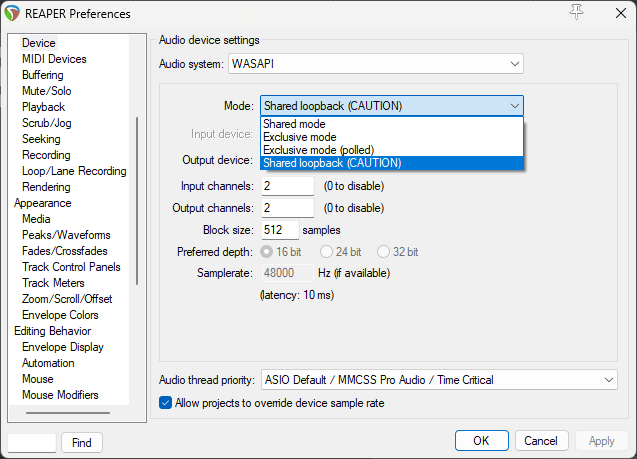

Here’s what it sounds like – the volume is set to max, the overdrive button is in, the tone is set at noon, and I’m playing an Agile LP clone via both pickups with volume and tone knobs at 7. Recorded into an iPhone balanced precariously on top of the Marshall speaker cab.